| |

|

|

|

|

|

The

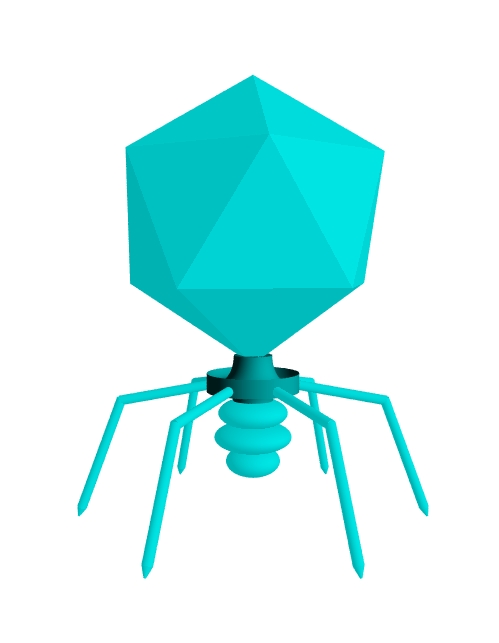

Molecular Architecture of Viruses

Above:

a podovirus, a virus which infects bacteria (a bacteriophage or

phage).

Viruses are superb molecular nanomachines! They are truly

minute, many around 100 nm or one ten millionth of a millimetre

in diameter and yet they have considerable structure. Recall

that they are essentially protein shells called capsids

enclosing genetic material (RNA or DNA, depending on virus

type). This genetic material contains a biological computer

program which reprograms the infected cell to make more copies

of the virus. The sole function of the virus particle or virion

is to deliver this genetic program to a suitable host.

A study of their form and function is an excellent way to convey

many aspects of molecular biology and biological physics. Such a

study conveys a strong sense of the adaptable and mechanical

nature of proteins and how the genetic code links to protein

form and function. Many aspects of virus biology can and have

been modeled by the application of physics, especially

thermodynamics, from assembly, DNA packaging, DNA injection and

membrane fusion. These make excellent student projects and for

this reason I wont give details here! I will give but one

example in brief: I recently had a group of students calculate

the entropy of virus capsid assembly using exact calculations,

which is quite an achievement due to the immense numbers

(factorials) involved, but made possible by modern computing

technology.

Advances in scientific methods have made possible detailed

analyses of virus structure and function. For example, cryo-EM

(EM = electron microscopy) in which samples are embedded and

frozen rapidly, e.g. in liquid nitrogen, and then sectioned and

imaged. Freezing removes artifacts introduced by chemical

fixation (the bonding of fixatives to such tiny structures may

distort them on a molecular scale and lowers resolution).

Similarly, using chemical stains to better visualise sections

also distorts structures, but digital processing of images

removes the need to use a stain in many cases. This allows a

visualise of structures almost intact and as they would appear

in life, but frozen in time. Many particles are visualised and

then a computer constructs an average image (thus increasing

signal to noise ratio). The computer can also stack imaged

sections to reconstruct a 3D representation.

Virus

Particle Assembly: packaging genetic material

The

above cutaway of the podovirus P22, which infects Salmonella bacteria, was modeled

in Pov-Ray based loosely on data published by Lander et al. (2006) obtained from

cryo-EM studies. The following is a summary of the stages in P22

virion (virus particle) assembly; 'gp' means 'gene product' and

refers to the various viral proteins, each of which has a

designated number, e.g. gp5 (blue) forms the main protein shell

or capsid enclosing the DNA

(which is double-stranded DNA in this virus). Some of these

proteins are structural, forming the body of the virion, as

shown above, whilst others are functional, assisting in the

reproduction of virions but not forming a part of the virion

infectious particle itself. The capsid of P22 is about 60 nm in

diameter.

One corner or vertex of the capsid is open and here is inserted

the portal

complex

(in red)

which is formed from 12 copies of gp1 and has a 12-fold axis of

symmetry. This creates a symmetry mismatch with the 5-fold

symmetry of the open capsid vertex in which the portal complex

is inserted. This complex allows DNA (green) to enter and leave

the capsid. The DNA is wound round as if on a spool. The DNA

towards the capsid wall forms three well-defined close-packed

layers of DNA which is almost crystalline. A simple calculation

can be done which predicts a pressure inside the capsid of about

20 atmospheres of pressure. DNA is negatively charged (it has

ionised phosphate groups along its backbone) and these charges

repel, such that it takes considerable force to pack naked DNA

so close together. Viruses utilise molecular

motors

to package their DNA so tightly. It has been suggested that the

portal complex rotates as DNA passes through it during

packaging, but this has not been proven. The DNA in the central

region of the capsid is less tightly packed, possibly because

DNA is reluctant to curve around in circles that are too small

and too tight.

The portal complex has been shown to have at least two distinct

conformations. Proteins can adopt different stable shapes or

conformations depending on how they interact with other

molecules. Changes in conformation involve movements of electric

charge through the protein structure, causing parts of the amino

acid chain making up the protein to flex or rotate as the

protein changes into another stable form. This likely involves

quantum tunneling and conformational change in a protein is

quite possibly a quantum mechanical event. When free, the portal

complex has a different conformation than when it is attached to

a packaged virion (Lander et

al.,

2006). One possible interpretation of this is an open and closed

state.

Assembly

of the P22 virion

Step

1

About

415 copies of the capsid protein gp5 assembles a procapsid with the help of about

300 copies of the scaffolding protein gp8; gp1 forms the portal complex.

Step 2

The

gp3/gp2 DNA packaging/terminase complex assembles on the gp1

portal complex and loads the procapsid with viral DNA through

the gp1 portal; gp2 is the large subunit of the complex and is

an ATP-powered molecular motor.

Step 3

Once

the capsid is full, it has been suggested that electrostatic

repulsion from coils of DNA surrounding the portal complex

triggers a conformational change (to the high pressure state)

closing the portal. The packaging complex stops loading DNA and

gp2 cuts the DNA (the viral DNA is produced as a concatemer or several copies

joined together in series); slightly more than one single copy

of the 41.7 kbp genome is loaded (1 kbp = 1000 DNA base pairs)

with each capsid head holding about 43.5 kbp. This strategy of

packing the head until it is full is called headful

packaging.

The procapsid expands into a larger, more icosahedral and

thinner walled mature capsid.

Step 4

The

gp3/gp2 complex dissociates and the tail complex proteins gp4

and gp10 attach to the portal complex, possibly helping to close

it. (Lander et

al.,

2006, identified additional material blocking the channel for

DNA ejection through the tail, which could be a protein. This is

shown in grey in the picture above).

Step 5

Six

trimers of gp 9 attach (trimer = group of 3 proteins bound

together in a specific conformation) to the tail complex. These

tail spikes are the 'legs' of the bacteriophage (these are not

locomotory but involved in adhesion to a target cell prior to

infecting it by injecting the viral DNA into the target cell

through the needle which is formed of gp26.

Ejection

Proteins (E Proteins)

Viruses

sometimes need to inject several proteins into their host along

with their genetic material. In P22, an estimated 12 copies of

gp7, 12 copies of gp16 and 30 copies of gp20 are incorporated

into the virion. These are ejected from the virion along with

the DNA during the infection process (along with a fourth

protein: gp26). Of these, gp16 and gp26 are directly involved in

DNA and protein ejection from the capsid. Proteins gp4, gp10 and

gp26 plug the portal in the packaged virion, but release the

blockage during DNA injection. The role of gp26 is to penetrate

the host cell membrane, allowing the viral DNA and ejection

proteins to enter.

In the diagram above, the ejection proteins (in purple) are

shown situated in a cylinder just above the gp1 portal as

suggested by Lander et

al.,

2006. This is speculative, cryo-EM gives the basic arrangement

of matter (and elemental analysis can be used identify the

make-up of the atoms giving rise to the EM image) but

identifying which protein is rich is problematic. Another

research group (Olia et

al.

2011) used Lander et

al.'s

cryo-EM data but carried out X-ray crystallography on isolated

gp1 complex to determine its shape and then superimposed this

onto the EM data and arrived at a different model summarised by

the diagram below:

The crystallographic analysis showed that the gp1 dodecameric ring had an upright tube accounting for the matter (electron density) attributed by Lander et al. (2006) to the ejection proteins. Which model is correct? Let us model the proteins in Phyre2 (Kelley et al., 2015) an online tool which builds theoretical models of proteins based on their known amino acid sequence. A single subunit of gp1 from a related virus, Salmonella phage ST160 (this virus is in the podovirus family and the gp1 proteins within this family are all similar):

Projecting from the main body or 'hip domain' of the protein is a long barrel domain (top) and a shorter leg domain (bottom right). The barrel consists of a single long alpha-helix (alpha-helices are shown in red) whilst the hip consists mainly of alpha-helices with some beta-strands (blue).

Above, a gp1 dodecamer modelled by docking the monomer prepared in Phyre2 with SymmDock (http://bioinfo3d.cs.tau.ac.il/SymmDock/). The barrel at the top projects into the virion.

Above:

the gp1 dodecamer seen from above (looking down along the

barrel).

Below: the gp1 dodecamer seen from below.

Below: the gp4 dodecamer (collar) as seen from above. The bottom of the gp1 dodecamer (the leg domains colored green in these models) fits into the top of this ring.

In our model, note that the tips of the barrel are splayed outwards. This could be an artifact of modeling, or is it real? Olia et al. (2011) depicted the barrel as a straight tube along its entire length and suggested that it makes up for the short tails of podoviruses by acting to smoothly accelerate the DNA during ejection (rather as a rifle barrel accelerates a bullet along it as the bullet is under sustained pressure). (essentially this would function as a DNA gun). Clearly, the ejection proteins and gp1 can not occupy the exact same space. The problem is that cryo-EM makes it hard to distinguish proteins from DNA, especially if the proteins are surrounded by DNA. If we allow the barrel to funnel outwards, however, then the ejection proteins could still occupy a central protein core above the gp1 funnel, perhaps something like this:

Wu et al., 2016, were aware of these interpretation problems and so they carried out an experiment to generate 'bubblegrams'. If a cryo-frozen sample is under the electron microscope beam for long enough, then the electrons damage the proteins, apparently knocking off hydrogen atoms which form bubbles of hydrogen gas. DNA, however, is largely unaffected and proteins wrapped in DNA bubble quicker since the DNA helps trap in the hydrogen gas. By measuring how long it takes for a bubble of gas to form when precisely irradiating the virion core, the location of the internal ejection proteins can be determined to quite a degree of accuracy. Wu et al. (2016) also tested mutant P22 lacking one or all of the ejection proteins. They concluded that the gp1 barrel does indeed form a funnel-like structure at its end with a core of ejection proteins above it, similar to our third model. Thus, the barrel is shorter than Olia et al. (2011) suggested and our DNA gun is more like a pistol than a rifle. perhaps the funnel helps guide DNA and proteins into the 'infection conduit, the hollow channel which carries them through the gp1 portal and out of the virion and into the host cell during infection.

Bacteriophage

Tail Fibres: binding to a potential host

Some

bacteriophages have much longer tail fibres, such as the T4

bacteriophage.

Above: the T4 bacteriophage. Note the long and jointed tail fibres and the needle-like 'feet' which bind to molecular targets (LPS and OMPC) on the target cell. This phage infects the bacterium Escherichia coli. Below is a molecular model of the foot. The globular collar (blue) is proximal and is connected to the needle-like domain which ends in the head domain at the bottom (green). This head domain is thought to fit into a pocket on the OMPC target protein. OMPC is an outer membrane protein in the outer membrane of Escherichia coli and forms channel pores (it is a porin consisting of a trimer of OMPC subunits). The foot is a trimer of gp37.

Below a 'ribbon-view' of the same model showing the 7 iron ions (in orange) which occupy the hollow core of the foot and hold the structure together. Each ion is bonded to 6 histidine residues which surround it (2 from each chain).

Images

taken of the 3D computer model provided by Bartual et al. (2010) and obtained

from the National Library of Medicine (NLM) MMDB database (Madej

et al. 2014). One of the

probable receptors for the T4 foot is the outer membrane protein

OmpC, a view of which is shown below. This model, as well as

that for the foot, is shown as represented in UCSF Chimera. The

source file for OmpC was downloaded from the NCBI protein

databank (PDB, National Library of Medicine (NLM)) and was

originally uploaded by Basle et

al.

2006 and obtained by X-ray diffraction of crystallised OmpC.

(The brown 'squiggles' are alkanes which co-crystallised,

presumably from the solvent; attempting to remove the solvent

with Chimera's dock prep tool was unsuccessful).

The T4 foot model also had some water solvent co-crystalised with it which was removed in Chimera before docking using PatchDock (Duhovny et al., 2002; Schneidman-Duhovny et al. 2005). This was an attempt to verify the findings of Bartual et al. (2010). The distal end of the foot (residues 932 to 959 on each of the three gp37 polypeptide chains). The highest scoring binding mode, highest scoring in that it gave the best geometric shape complementarity score (i.e. the best fit by matching the shape of the binding region on the foot with that on OmpC) confirmed their result. This showed that the most favourable model is for the foot to fit into the depression between the three OmpC subunits on the extracellular side.

OmpC belongs to a class of proteins called porins. Each subunit forms a barrel-like structure and sits upright in the bacterial outer membrane (which contains phospholipids in its inner leaflet and LPS in its outer leaflet) with the pore spanning the membrane, allowing molecules that are small enough (and water soluble enough) to cross the outer membrane freely. Three such pores fit together to form the porin molecule and the T4 foot tip docked preferentially in the middle of the three trimers on their outer face.

A divalent cation, such as calcium, has been shown to bind to each porin subunit on its outerside towards its outer face which acts as a binding site for the LPS lipids of the outer membrane (Arunmanee, et al. 2016). The model of OmpC we have used crystalised with a magnesium ion in a similar position and this formed three electrostatic bonds with the T4 foot (to lysine 945, glycine 942 and asparagine 959).

Capsid

Architecture

The

part of the virion forming a protective shell enclosing the

genetic material is the capsid. This is made up of

protein subunits called capsomeres. The exact arrangement

of the capsomeres varies considerably. Viral capsids have

variable geometry, but many approximate an icosahedron which may

be angular or expanded so as to approximate a sphere, depending

on virus type. A regular icosahedron consists of 20 equilateral

triangular faces and 12 vertices. In icosahedral viruses these

subunits typically exist in one of two states: pentamers of five

polypeptide subunits occur at the 12 vertices (sometimes one

vertex is modified as a portal vertex through which genetic

material is inserted during packaging when the virion is

assembled). Hexamers of 6 polypeptide subunits occur on the

faces and edges of the capsid. The individual proteins or

polypeptides making up the capsomeres (hexamers and pentamers)

are sometimes called protomers. The model below illustrates a T

= 16 capsid.

Above:

a T = 16 icosahedral capsid centered on a hexamer (left) and a

pentamer vertex (right). It is possible to move from one vertex

to an adjacent vertex by moving 4 capsomeres in a straight line

(4 x 4 = 16, hence the triangulation number, T, is 16). An

example of such a virus is herpesvirus

(accept that the herpesvirus capsid also has skew, see below). This model is

simplified since it ignores the interactions between capsomeres.

The assembly of viral capsids is a remarkable process. In some cases the same protomer will

fit into pentamers and hexamers and a single sufficiently

flexible protein subunit is often all that is needed to assemble

the viral capsid. Engineers adopt similar solutions when

constructing geodesic domes which have a similar architecture:

many copies of a single structural subunit can assemble the

dome, which is also very strong because of its use of triangles.

Other capsids are, however, more complex and some require

temporary scaffolding proteins for their assembly. Remarkably,

some of these complex structures will assemble spontaneously due

to the large entropy increase when ordered water molecules

surrounding isolated proteins in solution become displaced as

the subunits 'snap' together, increasing the disorder (and hence

the entropy) sufficiently for the process to be spontaneous.

Some viruses, however, require an extra energy source such as

ATP for capsid assembly.

It is possible to model or calculate the Gibbs free energy

change for capsid assembly in some cases. The equations are

shown below (e.g. see Katen and Zlotnik, 2009):

For

example, hepatitis B virus (HBV) has a (T = 4) capsid composed

of 120 subunits, each of which is a dimer (making 240 protomers

in total) giving N = 120. The above analysis was carried out on

HBV by Ceres et

al.

(2004). Since they are dimers they have a two-fold symmetry

axis, giving j = 2. Each dimer makes contact with 4 neighbouring

dimers, so C = 4 and CN/2 = 240 (the factor of 1/2 accounts for

the fact that each subunit accounts for half a contact). Almost

all synthesised capsomeres end up incorporated into a capsid so

the final concentration of dimer is very low. Using sensible

values for this allows the association constant for capsid

assembly to be obtained and the change in Gibbs free energy to

be calculated.

An unusually high degree of accuracy is required for this

calculation (standard spreadsheet packages will fail as well

conventional computational methods due to underflow/overflow)

and an approximation method can be used, however, the Wolfram

language used to be able to carry out the calculations rapidly

and gave the expected answers (though I have no guarantee of its

accuracy the answers were in the right ball-park

and the trends given were sensible)

but recent changes to the Wolfram language means that it will no

longer carry out these calculations at all,

at least not by default (there may be settings that can be

adjusted somewhere but I have not found them). Java can process

large numbers using its BigDecimal class, however, this class

does not incorporate functions to raise a BigDecimal to a power

or to take the natural logarithm of such a number. Cornell

University's BigDecimalMaths class contains such code, and the

power calculation can be carried out but it still lacks the

precision needed to compute the logarithm! (Maybe the method of

computation can be tweaked to make it more accurate?). For HBV,

the calculation in Wolfram

gave a result of around -10

kJ/mol. This is appreciably less than

zero and the capsid is predicted to self-assemble, driven by

entropy.

Each vertex has pentagonal symmetry: its is surrounded by 5

triangular faces. Each face is made up of protein subunits

called capsomeres (each capsomere may consist of one or more

protein subunits). Each triangular face is made up of one or

more basic traingular units, each such basic triangle consists

of 3 capsomeres. In the simplest case, each facet consists of a

single basic triangle. In adenovirus, for example, each facet

consists of 25 basic triangles. A capsomere with 5-fold

symmetry, called a pentamer, sits at each vertex, whilst

capsomeres with 6-sided symmetry (hexameres) sit along the edges

and make up the face itself. With 3 pentameres plus 18 hexameres

in each face (21 capsomeres in total) we can fit 25 basic

triangles in each. The triangulation

number (T)

is the number of such basic triangles which can fit into one

face of the icosahedron. For the simplest capsids, T = 1, for

adenovirus T = 25.

Above:

one facet of adenovirus is made up of 21 capsomeres which

sit at the vertices of 25 basic (imaginary) triangles giving T =

25. Note that since some capsomeres occupy the edges and

vertices of the icosahedron, the total number of capsomeres is

not simply 20T, but works out to be 10T + 2 or 252 in this case.

(Alternatively, we can take n as the number of

capsomeres

along one edge (6) and use the formula given above with n.

Not all viruses share this theme, since some have a skewed capsid

geometry.

In general the triangulation number is obtained on a triangular

0or hexagonal) grid with two axes, k and h. We then place a

capsomere in each hex (or at the apex of each triangle, see

below) and count how many capsomeres we need to move along h and

then k to move from one vertex (pentamere) to another vertex

(pentamere). We then apply the formula: T = h^2 + hk + k^2 to

find T. This is illustrated for some viruses below:

When the capsid is 'skewed' the hexameres are no longer arranged with their midline along the edges. An example of this is the T4 bacteriophage head. The T4 head is an elongated (prolate) angular icosahedron with rounded edges and is about 86 nm wide and 119.5 nm long. There are 5 equilateral faces forming each 'end-cap' and 10 elongated faces forming the mid-section (20 faces in total) and one vertex contains the phage neck which attaches to the tail rather than a usual pentamere. If we look at one of the end faces we see that it corresponds to T = 13l, where l means laevo' or left-handed. This is because in going from one vertex to the other, we take 3 paces along h (h = 3) and then one pace along k to the left (some viral capsids can be right-handed or 'dextro' (d). This gives a triangulatin number T = 3^2 + (3 x 1) + 1^2 = 9 + 3 + 1 = 13. This is illustrated below:

In

T4, each capsomere is made up of viral proteins: the protein

gp23 (gp = gene product) has a piece cleaved off to form the

active gp23*, 6 subunits of which make up the bulk of the

hexamere (shown in cyan), whilst gp24 is similarly modified to

form gp24*, 5 copies of which make up each pentamere (shown in

red). The proteins gp23 and gp24 are cleaved during head

maturation by a viral protease. The viral protein Soc stabilises

the capsid and forms hexagons around the gp23* (shown as green

dashed line). One copy of the protein Hoc occurs in the centre

of each hexamere (shown in yellow). In total there are 960

copies of gp23* (forming 160 hexameres), 55 copies of gp24* (5

per vertex with the 12 vertex occupied instead by a portal

protein complex), 840 copies of Soc and 160 copies of Hoc.

The elongated facets of the mid-section of the T4 head have T =

20. The rule for deriving this number is different than that for

an equilateral facet and is illustrated below:

Viruses do not simply have structural proteins that passively deliver a genetic cargo to a host cell. They also have working parts, some of which are incorporated into the virion infectious particle, others of which are used inside the host cell to gain control of host cell machinery and manufacture more virus particles.

One of the most intensively studied components of virus gadgetry is the packaging motor of dsDNA viruses (those viruses which have double-stranded DNA genomes). DNA is negatively charged, but despite this viruses can package their DNA into their capsids to near crystalline densities: the packaged DNA largely assumes a regular crystalline lattice. This packaging requires a molecular motor. Such motors belong to a class of powerful molecular nano-motors. These motors have drawn the interest of scientists and engineers from a wide range of backgrounds.

One of the most intensively studied of these nano-motors is that of bacteriophage phi29. This tiny bacteriophage has a very powerful and efficient DNA packaging motor, a copy of which assembles on a newly formed viral shell or capsid, pumps it full of the necessary DNA and then disassembles. Before looking at the structure of this motor, let us introduce phi29.

Above: The Bacteriophage phi29. This bacteriophage is a parasite

of the bacterium Bacillus subtilis. It consists of a head

some 54 nm in width and a short non-contractile tail 38 nm long. The

head is adorned by 55 head fibers (green-blue). Each of these head

fibers is a trimer of three gp8.5 (gene product 8.5) polypeptides.

These fibers or spikes have an uncertain function. Bacillus

subtilis is a Gram positive bacterium and the tail binds to

teichoic acids in the target cell wall (teichoic acids are

characteristic of Gram positive cell walls). The tail then

enzymatically digests the teichoic acids, bringing teh phage in

proximity to the peptidoglycan cell wall of the target Bacillus

cell. The tail then penetrates the cell wall and host cell membrane

by an uncertain mechanism, delivering its cargo into the target

cell.

The tail is connected to the head via the portal connector, a

dodecamer of 12 subunits of gp10. DNA moves into the capsid through

this portal during packaging and moves out through it during DNA

release in infection. The tail tube and lower collar are made from

gp11, the lower collar bearing 12 pre-neck or tail fibers (gp12 in

orange). The end of the tail is made of gp9.

The genome of phi29 encodes at least two different molecular motors: DNA polymerase (gp2)and the DNA packaging motor. DNA polymerases are ring complexes with a narrow central channel which moves along a single strand of DNA. This motor rotates relative to the DNA as it moves along it: it is a rotation motor. In contrast, the packaging motor is designed to translocate a double strand of DNA and has a much wider channel. The packaging motor consists of a ring of 5 or 6 copies of gp16 (shown in yellow; different studies disagree on whether the ring is a pentamer or hexamer) attached via a ring of 5 or 6 RNA molecules (prohead RNA or pRNA, shown in purple, one pRNA per gp16 subunit) (there is one pRNA per gp16 monomer) to the gp10 connector.

Above: during packaging the pRNA (purple) assembles on the

connector (a dodecamer shown in blue). One function of the pRNA is

to provide a scaffold for the attachment of the gp16 subunits

(yellow). Here we have modeled gp16 and the pRNA ring as hexamers.

The pRNA and gp16 both disassemble upon completion of packaging a

single copy of the genome inside the capsid: they do not form part

of the mature virion.

Unlike DNA polymerase (and other molecular motors which move along

single-stranded DNA)the packaging motor is not a rotation motor: it

does not spin on its axis during packaging. The gp16 provides energy

in the form of ATP. This energy is used to load the DNA by a revolution

motor mechanism. The DNA is passed from gp16 subunit to

subunit, such that the DNA strand revolves around inside the wide

channel through the center of the motor. This mechanism is thought

to optimise energy efficiency and also to prevent coiling or

tangling of the dsDNA. Each subunit obtains energy from ATP

hydrolysis and experiments suggest that the energy is stored upon

ATP hydrolysis and released when the products of ATP hydrolysis (ADP

and Pi) are released. Some research suggests that as many as four of

the 5 or 6 gp16 subunits may load with ATP prior to a burst phase,

during which DNA pumping occurs. Alternative models have sequential

ATP binding and hydrolysis occurring subunit by subunit. During each

burst phase one complete turn of the DNA helix (about 10 bases) is

loaded as the DNA revolves from gp16 subunit to subunit.

The motor must clearly be very strong to package the negatively

charged DNA to ~crystalline densities in order to overcome the

electrostatic repulsion. Indeed, the pressure inside the fully

packaged capsid can be about 20 to 30 atmospheres in small dsDNA

viruses. A 'back of an envelope' calculation, assuming the DNA to be

packaged in an hexagonal array (with a distance of 4 nm from the

centre of one strand to the center of each neighbouring strand)

gives the correct pressure (about 20 atmospheres when the

experimental fact that 75% of the negative charges on the DNA

backbones are expected to be neutralised in physiological saline.

DNA is a flexible molecule and winding it up into a close-packed

lattice also increases its entropy, but this is a minor contribution

compared to electromagnetic forces.

Only the phi29 family of phages have an RNA component of their

motor. In other bacteriophages the motor components are entirely

protein. The functions of the pRNA are not fully understood, but

apart from providing a scaffold for gp16, it has been shown to be

important in packaging the DNA the right-way round (left-end first,

i.e. ensuring correct directionality) and in ensuring that

only a single copy of the genome is packaged (restriction)

and also in ensuring the correct DNA is packaged (selectivity).

An important feature of this motor is that the gp16 ATPase subunits

must coordinate their activity. In one model, ATP hydrolysis at one

subunit causes a conformational change in the subunit, which extends

an arginine finger into the active site of the next subunit

in the cycle, forming a temporary dimer. This could potentially

either facilitate ATP binding or hydrolysis of an ATP molecule

already bound. Each subunit is bound, in turn, to the negatively

charged DNA molecule, presumably via positive charges, and upon

hydrolysis the DNA detaches and moves to the next subunit. Either

the subunit simply hides its positive charges or exposes negative

charges to actively push the DNA along. Various models of DNA

packaging motors in bacteriophages envisage the movement of

positively charged amino acid residues, as the motor proteins change

conformation, to push or pull the DNA into the capsid. In phi29,

once packaging is complete, a protein gp3 plugs the channel in the

center of the tail, acting like a plug. However, the connector gp10

may also act as a one-way valve to prevent the DNA slipping back out

during packaging. In this case, gp10 would have to undergo a

conformational change to allow the DNA to exit during infection.

Presumably the mechanism of the DNA packaging motors of

bacteriophages all operate along similar principles, though they

clearly differ in terms of power. The fastest and most powerful

packaging motor known probably belongs to the T4 bacteriophage. Here

we shall take a look at a model for the action of this motor, based

on work by Sun et al. (2007, 2008). This model is similar to

the one discussed above for Phi29 above, but considers only an

isolated subunit of the ATPase motor, gp17 in this case, and has the

arginine finger activating its own subunit. Let us look at the

arrangement of the motor that assembles at the portal vertex of the

T4 procapsid during phage packaging. The layout is illustrated

below:

Above: top left a diagram of the procapsid into which DNA is pumped via the open vertex at the bottom, the portal vertex. Bottom left: an illustrated section through the portal vertex. Right: gp17 rings viewed from below and superimposed (bottom right). Again, the structures of crystallised proteins (determined by X-ray diffraction by Sun et al. 2008) have been superimposed on electron density images to elucidate the configuration. In this model the symmetry of gp17 is assumed to be fivefold: that is five gp17 subunits form a ring, in fact a double ring (Ring A and Ring B in the figure above, which is based on Sun et al. 2008). (There is empirical evidence supporting this assumption). Each gp17 (TerL) subunit consists of three principle domains: near the N-terminus the N-subdomains 1 (green, outermost) and N-subdomain 2 (cyan, innermost) form the A-ring. The C-terminal domain (orange) forms the B ring. The gp17 rings dock to the portal proteins (gp20, probably a dodecamer or ring of 12 subunits shown in red). The C-domains form a nozzle like structure into which the DNA (shown as the double helix) is threaded into the capsid. The gp17 rings form the large terminase complex, and there is an additional ring of gp16 (TerS) subunits which dock onto this, forming the small terminase complex, but this is not shown here. Below I modeled a published sequence (NCBI P17312.1) of gp17 in Phyre2. The results agree essentially with published structures determined by X-ray diffraction:

In this model I have already docked a molecule of ATP (using AutoDock Vina in UCSF Chimera) which is bound to the correct ATP-binding pocket (though not necessarily in the right orientation: more on that later). Amino acid residue 162 (counting from the N-terminus as is the convention) is arginine (R or Arg)and is shown as part of the first N-terminal subdomain. This shows just one gp17 subunit, when five join together in a ring, the C-domains will form the external nozzle or opening through which DNA is threaded. ATP is the cell's energy currency and supplies the energy needed by the motor, being hydrolysed (reacted with water) to form ADP and Pi (Pi = inorganic phophate). ATP binds to N-subdomain 1 where it is hydrolysed. When the products, ADP and Pi, exit the active site the energy is released as movement of the gp17 monomer. This is illustrated below:

The movement involves a six degree rotation of N-subdomain 2, as

shown by the curved arrow in orange. This brings positive and

negative charge pairs on N-subdomain 1 and the C-domain into

alignment, causing an attractive electrostatic or Coulomb force

to act between these subunits pulling the C-domain up towards the

N-domain. During this motive phase or power stroke the viral

DNA is bound to the C-domain, probably to the green loop as shown,

by other electrostatic forces and hence is lifted further into the

procapsid during the power stroke. This subunit then goes into a

relaxation phase, relaxing and unbinding from the DNA which is

electrostatically repeled and/or attracted towards the next adjacent

gp17 subunit in the pentamer (five subunit) ring. In this way the

DNA is kept hold of at all times and there is little slippage out

from the procapsid.

Eventually, a full copy of the genome (plus a bit) is packaged into

the procapsid shell and then DNA is then cut by gp17 assisted by

gp16. (The viral DNA is copied as a concatemer of several

copies of the genome, end-to-end in one DNA molecule and so every

time a capsid fills the concatemer must be cut). Assembly of the

tail then commences and the DNA is plugged and kept firmly inside

the maturing capsid. Several forces resist DNA packaging especially

when the capsid is nearly full. The main one is electrostatic

repulsion: DNA has a negatively charged phosphate backbone and

packing DNA to the near crystalline density of the full capsid menas

pressing these negative charges together. A calculation can be done

to show that this electrostatic repulsion yields internal

capsid pressures of the correct order of magnitude (about 10 times

that in a corked champagne bottle; I may show this calculation

later) once the fact that a substantial fraction of the negative

charges are neutralised by positively charged ions (under

physiological conditions) has been taken into account. Additional

forces arise from the stiffness of the DNA which must be folded up

tightly and from entropy. The contribution from entropy is

because DNA is a 'wriggly' molecule and likes to spread itself a bit

by thermal motion, whereas packaged DNA is restricted and forced to

stay closely packed. However, the contribution from entropy is only

about one-tenth that of electrostatic repulsion.

Note the dominance of electrostatic forces: the DNA packaging gp17

machine is an electrostatic motor. This illustrates the

dominance of electrostatic forces at the molecular scale. The motor

is also not strictly a rotor: it was once speculated that the

packaging motor rotated about its axis as DNA corkscrewed into the

capsid. This is not the case since the DNA is passed from subunit to

subunit around the circle (pentagon)(there are rotary molecular

motors that process DNA but for other purposes). However, it is also

not simply a linear motor: it does not simply pull or push the DNA

inside in a straight line. It is something inbetween these two motor

types, let us call it a rotary-linear motor.

Now, let us look in more detail at the binding and hydrolysis of the

ATP. I have simulated the binding of a molecule of ATP to a single

subunit of gp17 (using AutoDock Vina in UCSF Chimera). The docking

software uses algorithms to find likely binding sites and likely

positions (poses) of the ATP within the binding site. It does find

the correct pocket but there are many poses within it: different

arrangements of the flexible ATP molecule within the pocket. I show

one of these poses below:

This is a ribbon view which represents the component

(secondary) structures of the gp17 protein as a series of sheets

(made up of arrows or beta-strands), coils (alpha-helices) which act

as rods/springs, and flexible hinges. The arrangement of these

structures in a given protein accounts for their physical mechanism,

but the electrostatic charges and chemistry of the particular amino

acid residues are also important. Note that the chain of three

phosphate groups of the ATP molecule (adenosine triphosphate) shown

in orange are held in place since the third terminal phosphate (the

gamma phosphate) has hydrogen-bonded (solid yellow line) to

the lysine 166 (Lys or K166) residue of N-subdomain 1 (shown in

purple). This is thought to happen in reality, since this lysine

residue is essential for efficient ATP hydrolysis (mutants lacking

it do not perform well). Indeed, the ATP binding-site contains two

structural motifs commonly found in ATP-binding proteins:

the Walker A and Walker B motifs.

The Walker A motif contains the phosphate-binding lysine residue and

is also called a P-loop or phosphate-binding loop. The

Walker B motif contains (ends in) a glutamate residue at position

256, Glu or E256 shown in grey. This residue is negatively charged

and activates a molecule of water to act as a nucleophile.

Glutamate is highly negatively charged and so can remove a

positively charged proton from a molecule of water to generate a

hydroxyl radicle or hydroxide ion which attacks the molecule of ATP

bound in the active site, being attracted to the phosphate atom in

the gamma phosphate, reacting with it to cleave the

phosphate-phosphate bound between the gamma and beta phosphates,

forming ADP + Pi. This bond breakage releases energy which is stored

by gp17 transiently and used in the subsequent power stroke. The

presence of the arginine finger (residue R162 in yellow) is required

to further destabilise the phosphate-phosphate bond for efficient

breakage. Whether the arginine finger of the same or a neighbouring

gp17 subunit is involved is another matter. Arginine fingers are

characteristic of proteins which hydrolyse ATP: the movement of the

arginine finger towards the ATP molecule acts as the final trigger

for ATP hydrolysis.

Other residues are also involved in binding the ATP to hold it in

the optimum pose for hydrolysis to occur. In this case the ATP has

also formed two hydrogen-bonds to the sidechain of Glu 198. This is

probably not the most likely mode of binding. First of all, docking

software is never guaranteed to find the optimum pose (if there is

one, the ligand, ATP in this case, may alternate between different

poses or perhaps exist in a superposition of poses) however, our

model has one other major shortcoming: ATPases like gp17 utilise an

ion of magnesium (or manganese) to help hold the ATP in place: they

bind to a magnesium-ATP complex or, in other words,

magnesium is a cofactor. We have not incorporated this into our

model. The functions of magnesium ions in ATP-hydrolysing enzymes

are:

1. To hold the ATP in a specific pose;

2. Neutralise certain negative charges to facilitate ATP binding;

3. Increase binding energy, i.e. make the binding of ATP more

spontaneous;

4. To assist in nucleophilic attack by utilising the

electron-withdrawing power of the Mg2+ ion, that is it is

a co-reactant.

I suspect that docking to ATP with the magnesium in place would

narrow down the number of favourable poses or binding postures of

the ATP molecule. Finally, bear in mind that the hydrolysis of a

single ATP molecule only provides enough energy to move about 2 base

pairs (2 bp) of DNA into the capsid. The T4 bacteriophage has to

package 171 000 bp (171 kbp) plus a bit into the capsid and does so

at a rate of about 2000 bp/s. Thus the gp17 pentamer hydrolyses

about 1000 ATP molecules each second, for about 86 seconds (assuming

constant velocity as the capsid fills). Thus each gp17 works in

turn, passing the DNA onto the next subunit and thus the DNA moves

around the gp17 ring more than 24 000 times to package a single

capsid. The motor will then detach as phage assembly continues and

may catalyse the packaging of more phages.

The techniques used to analyses the nanomachinery of viruses is also

being increasingly used to study machinery in bacteria (such as the

flagellum, pilus and sensory apparatus) and will no doubt be used in

other organisms too, including human cells. what is especially

interesting is that we are beginning to really appreciate how

proteins function as mechanochemical nanomachines! Viruses furnish

us with excellent examples of this.

Epsilon15 Phage and Building a Capsid

Epsilon15 is a Podovirus infecting the bacterium Salmonella anatum Studies conducted into its capsid structure provide an insight into how capsids of dsDNA phages (and perhaps other dsDNA viruses such as herpesevirus) in general are put together. The head (enclosing the dsDNA) is icosahedral. This virus has a triangulation number of 7, making the capsid a skrew-type capsid, in this case T = 7laevo (that is h = 2, k = 1). The main capsid protein of many dsDNA viruses is similar in shape, containing a characteristic fold of the polypeptide chain, despite the wide variation in amino acid sequence. Viruses evolve rapidly so sequence similarities are rapidly lost, however, constraints on function mean that if a capsid protein substitutes its amino acids over the course of evolution, that the substitutions will be such as to presever the key functional form of the protein. This is the case with certain other viral proteins too. A longitudinal section through epsilon15 is shown below:

The capsid or shell of the head has been studied by cryo-electron microscopy and computer modeling and the results loaded to the PDB (Protein Data Bank) reference NGL Viewer (AS Rose et al. (2018) NGL viewer: web-based molecular graphics for large complexes. Bioinformatics doi:10.1093/bioinformatics/bty419), and RCSB PDB. Some representative views of this model are shown below:

In this model the head has been modeled as a complete icosahedron with 12 penton vertices, but in reality one of these vertices will be the portal vertex connected to the tail attachment and injection machinery. This icosahedral cpasid is made up of the major capsid protein gp7 and the minor capsid protein gp10. Each triangular face of an icosahedral capsid can be split into three imaginary asymmetric units containing a number of protein subunits equal to teh triangulation number, 7 in this case, so each asymmetric unit of the Epsilon15 bacteriophage is made up of 7 gp7 protein molecules. The structure of a single gp7 protein is shown below (modeled in Phyre2 using an amino acid sequence retrieved from the NCBI database (NCBI NP_848215.1) containing the full 335 amino acid residues and modeled by Phre2 with almost 100% confidence,

The top panel shows the ribbon view, the bottom panel the surface filling view (images generated in UCSF Chimera). The protein can be divided up into a number of regions as labeled, but of particular importance to our discussion is the E-loop. The gp7 subunits must occupy two quite different environments: in groups of 6 to form the hexons making up each capsid face and in groups of 5 as pentons making up each vertex (apart from the portal vertex). These similar but different positions are called quasi-equivalent and an important consequence of this is that if teh capsid is to be economically constructed using a single protein, then this protein must be flexible to fit into these different positions, and accommodate differing angles of curvature. The Epsilon15 gp7 capsid protein has a characteristic fold, which is typical of thsi type of virus and allows the E-loop to hinge downwards towards the interior of the capsid to varying degrees to obtain a best fit wherever it is in the capsid. The E-loops of subunits in the pentons hexons adjavent to these can bend downwards by up to 20 degrees. The asymmetric unit making up part of an icosahedral facet, consisting of seven gp7 subunits is shown below (approximate) - the hexon capsomere formed by 6 subunits is readily apparent:

Notice how the E-loops overlap the adjacent subunit (overlapping its N-arm and P-domains. Notice also that teh A-domains point towards the centre of the hexagon and interact with one-another via electrostatic forces. Where gp7 subunits meet at 3-fold and 5-fold axes of symmetry two positively charged arginine amino acid residues at the end of the E-loop of one subunit form ionic bonds to a negatively charged hook on a subunit in an adjacent capsomere, strongly binding adjacent capsomeres together. (In the phage HK97 which infects the bacterium Escherichia coli has a similar arrangement except that the ionic bonds are replaced by covalent disulphide bridges. This arrangement in Epsilon15 does not give the capsid enough strength to resist the enormous internal pressures of the tightly packed DNA inside the mature head. This is where the minor capsid protein gp10 comes into play. Each hexon is surrounded by 6 pairs of gp10 which form detectable bumps on the outside of the capsid (along edges of local 2-fold symmetry, which do not correspond exactly to the 2-fold axes in an ideal icosahedron). The gp7 E-loop forms three ionic bonds to gp10 and the two gp10 subunits in the gp10 dimer interact via hydrophobic interactions. Furthermore, the gp10 dimers are buttressed between the n-arms of the gp7 subunits. Each asymmetric unit this consists of 7 gp7 subunits and 6 gp10 dimers. The gp10 dimers have been described as molecular staples holding adjacent capsomeres together and giving the capsid additional strength.

More virus architecture - Spike proteins and how antibodies disable them

References

Arunmanee

W., M. Pathania, A.S. Solovyova, A.P. Le Brunc, H. Ridley, A.

Baslé, B. van den

Berg, and J.H. Lakey, 2016. Gram-negative trimeric porins have

specific LPS binding sites that

are essential for porin biogenesis. PNAS E5034–E5043.

Baker, M.L., C.F. Hryc, Q. Zhang, W. Wu, J. Jakana, C.

Haase-Pettingell, P.V. Afonine, P.D. Adams, J.A. King, W. Jiang

and W. chiu. 2008. Validated near-atomic resolution structure of

bacteriophage epsilon15 derived from cryo-EM and modeling. PNAS

pnas.1309947110

Bartual, S.G., J.M. Otero, C. Garcia-Doval, A.L. Llamas-Saiz, R.

Kahn, G.C. Fox and M.J. van

Raaij, 2010. Structure of the bacteriophage T4 long tail fiber

receptor-binding tip

Proc. Natl.

Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 107:

20287-20292.

Basle, A., G. Rummel, P. Storici, J.P. Rosenbusch and T.

Schirmer. Crystal structure of

osmoporin OmpC from E.

coli

at 2.0 A. J.

Mol. Biol.

362: 933-942.

Bustamante, C. and J. R. Moffitt, 2010. Viral DNA Packaging: One

step at a time. In: Gräslund A., Rigler R., Widengren J. (eds)

Single Molecule Spectroscopy in Chemistry, Physics and Biology.

Springer Series in Chemical Physics, vol 96. Springer, Berlin,

Heidelberg.

Ceres, P., S.J. Stray and A. Zlotnik, 2004. Hepatitis B virus

capsid assembly is enhanced by

naturally occurring mutation F97L. J.

Virol.

78: 9538-9543.

Jiang, W., M.L. Baker, J. jakana, P.R. Weigele, J. king and W.

Chiu. 2008. Backbone structure of the infectious e15 virus

capsid revealed by electron cryomicroscopy. Nature 451:

1130-1135.

Katen, S. and A. Zlotnik, 2009. The thermodynamics of virus

capsid assembly. Methods

Enzymol.

455: 395-417.

Kelley, L.A., S. Mezulis, C.M. Yates, M.N. Wass and M.J.E.

Sternberg, 2015. The Phyre2 web

portal for protein modeling, prediction and analysis. Nature Protocols 10: 845-858.

Lander, G.C., L. Tang, S.R. Casjens, E.B. Gilcrease, P.

Prevelige, A. Poliakov, C.S. Potter, B.

Carragher and J.E. Johnson, 2006. The Structure of an infectious

P22 Virion Shows the Signal

for Headful DNA Packaging. Science 312: 1791-1795.

Lin, S., T.I. Alam, V.I. Kottadiel, C.J. VanGessel, W.-C. Tang,

Y.R. Chemla and V.B. Rao, 2017. Altering the speed of a DNA

packaging motor from bacteriophage T4. Nucleic Acids

Research 45: 11437-11448.

Madej, T., C.J. Lanczycki, D. Zhang, P.A. Thiessen, R.C. Geer,

A. Marchler-Bauer and S.H.

Bryant, 2014.. MMDB and VAST+: tracking structural similarities

between macromolecular

complexes. Nucleic

Acids Res.

42 (Database Issue): D297-303.

Olia, A.S, P.E. Prevelige Jr., J.E. Johnson and G. Cingolani,

2011. Three-dimensional structure

of a viral genome-delivery portal vertex. Nat. Struct. Mol.

Biol. 18: 597-603.

Rao, V.B. and L.W. Black, 2010. Structure and assembly of

bacteriophage T4 head. Virology J. 7: 336.

Sun, S., K. Kondabagil, P.M.Gentz, M.G. rossmann and V.B. Rao,

2007. The structure of the ATPase that powers DNA packaging into

bacteriophage T4 procapsids. Mol. Cell 25: 643-949.

Sun, S., K. Kondabagil, B. Draper, T.I. Alam, V.D. Bowman, Z.

Zhang, S. Hegde, A. Fokine, M.G. Rossmann and V.B. Rao, 2008.

The structure of the phage T4 DNA packaging motor suggests a

mechanism dependent on electrostatic forces. Cell 135:

1251-1262.

Wu, W., J.C. Leavitt, N. Cheng, E.B. Gilcrease, T. Motwani, C.M.

Teschke, S.R. Casjens,

A.C. Steven, 2016. Localization of the Houdinisome (Ejection

Proteins) inside the

Bacteriophage P22 Virion by Bubblegram Imaging. MBio. 7(4): e01152-16.

Xiang Y, Rossmann MG. Structure of bacteriophage phi29 head

fibers has a supercoiled triple repeating helix-turn-helix

motif. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108(12):4806-10.

Zhao, Z., G. M. De-Donatis, C. Schwartz, H. Fang, J. Li and P.

Guo, 2016. An arginine finger regulates the sequential action of

asymmetrical hexameric ATPase in the double-stranded DNA

translocation motor. Mol. and Cellular Bio. 36:

2514-2523.

External

links

Phyre2

http://www.sbg.bio.ic.ac.uk/~phyre2/html/page.cgi?id=index

PatchDock

https://bioinfo3d.cs.tau.ac.il/PatchDock/

SymmDock

http://bioinfo3d.cs.tau.ac.il/SymmDock/

Wolfram

Language

http://wolframlanguage.org/

Article created: 2 April 2018

Article updated: 7 April 2018

Article updated: 22 April 2018

Article updated: 5 Nov 2018

Article updated: 22 Jan 2019

Article updated: 30 Apr 2019

Check back for updates